Blackout report blows away big myths about role of wind energy

The latest report into the South Australia blackout by the Australian Energy Market Operator has blown away two of the biggest myths about wind energy that its critics were using as reasons for the state-wide outage.

Within hours of the lights going out in South Australia, mainstream media, state and federal Coalition parties, and anti-wind interests in business and politics were blaming the “intermittency” of wind energy and its inability to generate power when the wind blew too hard.

If it wasn’t obvious to most people almost immediately that these were not factors in the blackout, then the AEMO report has certainly put them to rest.

“The most well known characteristic of wind power, variation of output with wind strength (often termed ‘intermittency’), was not a material factor in the events of 28 September 2016,” AEMO notes in its report.

And it wasn’t the fault of excessive wind speed either. That was the immediate accusation of the ABC’s Chris Uhlmann and Nick Xenophon in the hour after the blackout occurred, and later by deputy prime ministerBarnaby Joyce.

“Forty per cent of South Australia’s power is wind generated, and that has the problem of being intermittent – and what we understand at the moment is that those turbines aren’t turning because the wind is blowing too fast,” Uhlmann told the ABC audience on radio and TV within an hour of the blackout.

That, if it wasn’t clear at the time, was also nonsense. The AEMO report says that excessive wind speed only affected 20MW of the more than 800MW of wind power operating at the time. And despite forecasting wind speeds of more than 120kmh, AEMO decided that it had no need to order any further back-up generation.

“This updated report from AEMO confirms that the intermittent nature of wind energy had nothing to do with the September blackout in South Australia,” energy minister Tom Koutsantonis said in a statement.

“There are a number of political opportunists that now owe South Australians an apology for using this event to pursue their anti-renewables agenda.”

It is, however, important to note that the role of 18 wind farms in the state – and its capacity of 1,500MW which accounts for around 40 per cent of total demand – was not exonerated by AEMO.

AEMO points the finger at the loss of 445MW of wind generation after six voltage disturbances and five system faults (after the loss of three major transmission lines) as the straw that broke the camel’s back for the interconnector, causing it to separate from South Australia and for the state to go “system black.”

There is some dispute about the role of this loss of generation – or whether the fault lay with the uncontrolled loss of voltage that was happening, anyway, all around them. AEMO notes that voltage levels fell to 40 per cent of normal levels after the last line was lost. Wind farm operators suggest no generator could ride through such falls.

But the AEMO report makes clear that if the ride-through limits were the cause, it is a technical issue, and it is not about the nature of the energy source. Specifically, this refers to the settings on the “self protect mechanisms” in the wind turbines that might have been the problem. It also notes that issue is easily fixed, and already has been in most of the wind farms affected.

It turns out that some of the wind farms had been programmed to stop generating after riding through only two faults, and stopped generating earlier in the 80 second crisis caused by the fall of three main transmission losses.

Others were programmed to stop after five or six – such as the relatively new Snowtown and Hornsdale wind farms – and continued until just before the separation, while some, either not impacted by voltage issues on the grid or with higher fault ride-through settings, rode through until all generators were disconnected when the interconnector separated.

The Waterloo wind farm was able to ride through five faults that occurred in its area because its ride-through maximum had been set at nine.

It turns out that the problem was not, as first thought, limited to Suzlon turbines, but also affected Siemens technology. Most of these wind farms, including Snowtown and Hornsdale, have adjusted their fault limit to around 20 and are back operating as normal.

AEMO is now investigating what limits are imposed on wind turbines elsewhere on the grid. But one question remains: if the generators and the market operator did not know of these limits before the blackout, as some suggest, then why not?

“The voltage shocks this weather caused led nine wind generators to reduce their output. AEMO has confirmed that the wind generators were not able to ‘ride through’ these sustained shocks because of factory settings that only allowed them to sustain between three and six voltage events,” Koutsantonis added.

“This is a software issue – not a problem with renewable energy. I am pleased that AEMO will now lead investigations at a national level to ensure all wind farms around the country have the appropriate settings they need to sustain the types of voltage shocks we can expect in Australia.”

Here is another graph and the AEMO explanation of what happened:

Wind turbines are designed so that upon detecting a low voltage at their terminals, the normal steady-state control is suspended and a sequence of actions is performed, referred to as fault ‘ride-through’ mode. The purpose is for the wind turbine to remain connected to the grid and provide support to the voltage recovery at the point of connection.

Wind turbine control systems are set to provide a fault ride-through response when voltage dips to below 80% to 90% of its normal voltage as seen at their low voltage terminals.12

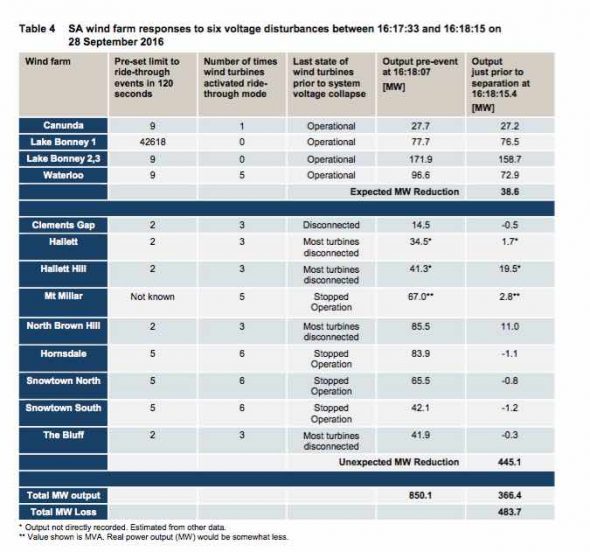

The size of voltage dips observed by SA wind turbines online at the time of the event was sufficient for ten of the thirteen wind farms online to activate their fault ride-through mode. Depending on the wind farm, this mode of turbine operation was activated between three and six times, as shown in Table 4.

Of the 13 wind farms on line prior to the event,13 four remained in service: Canunda, Lake Bonney 1, Lake Bonney 2 & 3, and Waterloo. Of these, only one (Waterloo) initiated ride-through mode multiple times, but it remained in service because it was set to a limit of more than six ride-through events.

The size of the voltage dips for wind farms connected to the South East region of SA, such as Lake Bonney and Canunda wind farms (Figure 7), was not as large as the voltage dips observed at Davenport (see Figure 4). Wind turbines in the South East region initiated fault ride-through mode either once, at around 16:18:15, or not at all.